The Possibility of Progress

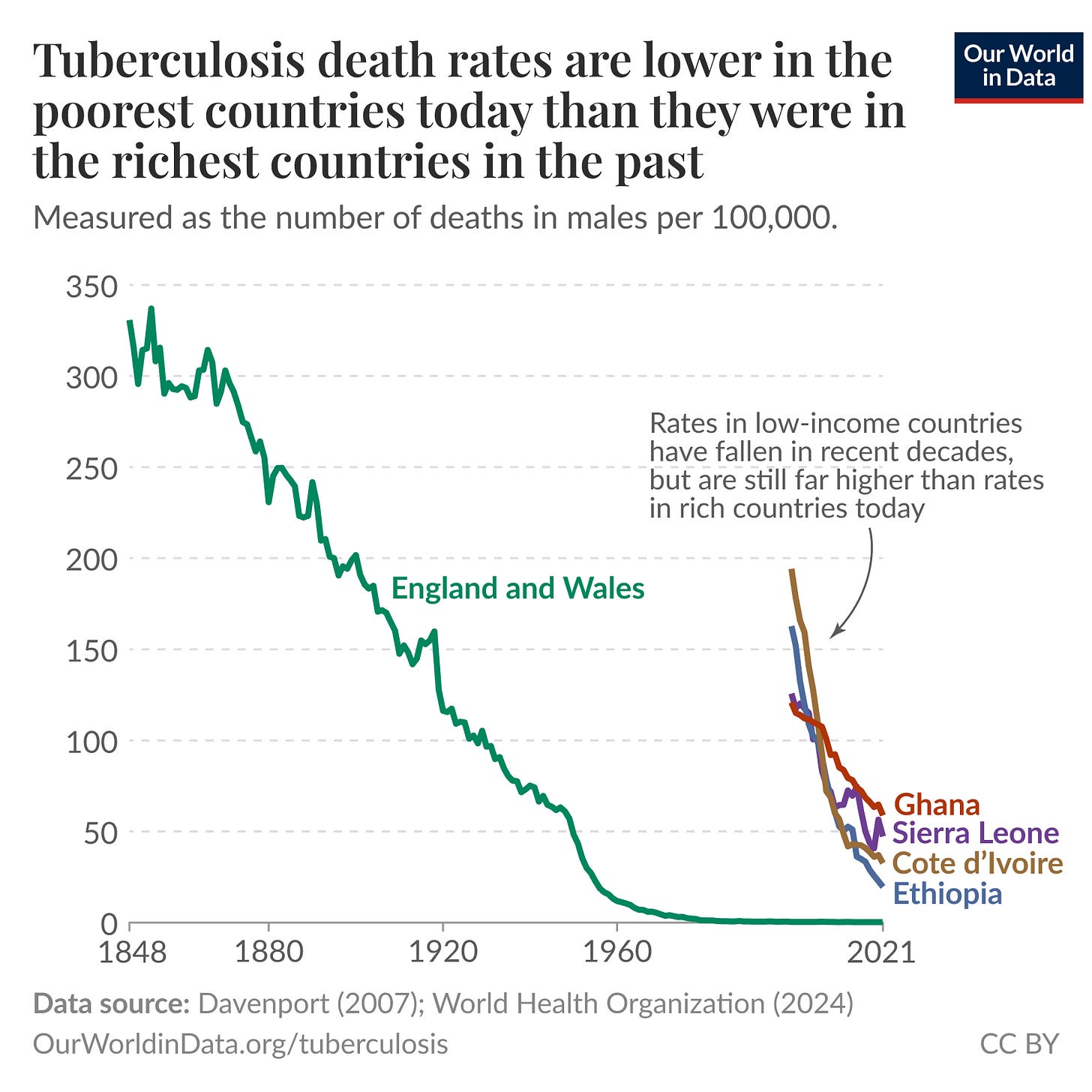

In their post for Our World in Data, Hanna Ritchie and Fiona Spooner leverage some compelling visuals demonstrating the historical decline of TB mortality in ‘rich countries’ to make the case that the same results can be achieved in LMICs.

They write:

You might wonder whether this progress in the US and Europe can be replicated elsewhere. We think it can, for a few reasons.

First, low-income countries have already made progress; TB death rates have fallen in recent decades. There’s no reason this has to stop. Second, death rates in the US and the UK were far higher in the past than they are in some of the worst-off countries today. There’s little reason why these countries can’t replicate what Britain did over the next 30 to 40 years.

It’s only by looking at the US or Europe’s history with tuberculosis that we know this change is possible. In the early 1950s, the death rate in the United States was 12.4 per 100,000 people. That’s not much less than the global average of 16 per 100,000 today.

Going further back in time, we saw that the human toll of the disease was far worse in historical London or New York than you’ll find almost anywhere in the world today. The fact that we either forget or are unaware of this means that this tragedy is not a given.

Digital Deployment

Arab News correspondent Sherouk Zakaria chronicles the remarkable progress the Iraqi government has made in detecting and treating tuberculosis nationwide, including amongst displaced populations.

Roughly five million displaced people have returned to their towns and villages since Daesh’s territorial defeat in 2017. But these areas often lack basic infrastructure, increasing the risk of TB outbreaks. In Mosul — Iraq’s second-largest city, which endured three years under Daesh — those unable to afford housing live in overcrowded settlements, where malnutrition and exposure to the elements weaken immunity.

Iraq’s NTP, supported by the International Organization for Migration, the Global Fund, and the World Health Organization, is tracking TB among displaced communities using advanced diagnostic technologies and artificial intelligence. [M]obile medical teams have been a game-changer for these vulnerable communities.

[Nationwide], [r]outine screenings by…mobile units helped to increase the detection rate of drug-resistant TB from 2 percent to 19 percent, and drug-sensitive TB from 4 percent to 14 percent between 2019 and 2024, according to IOM data.

Addiction Challenges

Journalist Charity Kilei investigates the role addiction plays in complicating TB treatment regimens, focusing on the experiences of patients hailing from Nairobi’s makeshift settlements.

James Mulwa grew up in Shauri Moyo, one of Nairobi’s densely populated informal settlements. When he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, he faced not only a health crisis but also deep social stigma.

From a young age, Mulwa had used substances such as chang’aa and marijuana. By the time TB struck, addiction had become part of his daily life. Abstaining from drugs and alcohol was not something he felt capable of—even during treatment.

“When you’re on TB medication, they tell you to stop using substances. But if you’re already an addict, it’s not that simple. Your friends come looking for you. They bring the drink because it’s what you’ve always done together,” James says.

Admitting he had TB felt like a death sentence—not just physically, but socially. His fear of revealing his diagnosis kept him silent. In the close-knit but often unforgiving environment of the slums, disclosure could mean social exclusion. And in a place where friendships often double as survival networks, isolation could mean going hungry.

Crackdown Ramifications

In her article for Politico, Alice Miranda Ollstein captures the concern some public health experts have expressed about the impacts of the recent scale-up of ICE raids on management of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases.

[P]ublic health leaders are concerned about the impact of Trump’s immigration policies on efforts to combat tuberculosis — a bacterial infection the U.S. nearly eradicated decades ago that is now resurging from Kansas City to Los Angeles.

“People are, all of a sudden, a little bit leery of presenting themselves in congregate settings where they might be targets for enforcement,” said Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials. “It really is emanating out of a greater fear of those places being actively monitored by ICE.”

The Trump administration and advocacy groups that want to restrict immigration say higher levels of tuberculosis in immigrant communities justifies turning people away at the border. But Freeman and other experts stress that while the infections are more prevalent in those communities, it has nothing to do with their country of origin and everything to do with crowded living conditions and a lack of access to vaccines, which is why TB outbreaks are also common in U.S. homeless shelters and prisons. By implementing policies that deter immigrants from seeking health services, she argued, the Trump administration could make the situation worse.

“We are worried, from a public health standpoint, that people will tie tuberculosis outbreaks to immigrant communities unfairly and traumatize those groups even more,” Freeman said. “We were fearful that it might be used by the administration to say, ‘This is a disease they bring in. We’ve got to get them out of the country.’”

Open Air Plan

In The Independent, geography professor John Harner explores the architectural legacy of tuberculosis in Colorado Springs.

As a result of the concentration of health seekers, Colorado Springs became a leader in services and innovations designed to serve lungers. Open air windows were an obvious treatment, but contraptions were also built to keep one’s head outside while the remainder of the body stayed in the warmth, and sleeping porches were a popular extension of the search for constant fresh air. Verandas and sleeping porches became regular architectural elements in many Colorado Springs homes.

Perhaps the most popular innovation was the sleeping hut, originally a tent, designed by Dr. Charles Gardiner, and commonly referred to as the Gardiner hut. Gardiner’s design was an octagonal wood floor with a canvas tent overlaying a wood frame. The walls were vertical for five feet, then the roof sloped inward with a conical shape. The tent had an opening at the top for air to escape, but the key was that the lower edges were fastened at one inch out from the floor, ensuring continual airflow.

In later years, the tents were converted to more permanent huts upgraded with shingle roofs and sturdier frames; canvas sides were eventually converted to wood and designed with the floor ventilation gone and only two opposing windows used for air flow. These more permanent structures abandoned the primary design element, that of the open seam along the floorboards with sealed foundations and merely relied on windows to circulate air, a seeming violation of the original design intent by Gardiner, but a popular modification nonetheless.

Crafting History

Staying on the topic of architecture, SF Gate writer Paula Mejia highlights the critical role tuberculosis - and evolving societal beliefs about hygiene - played in sustaining interest in the popular Craftsman home design style.

The late 1800s saw an influx of transplants, many of them from the Midwest and East Coast, to sanatoriums that had cropped up around Southern California in places like Altadena, the surrounding San Gabriel Valley and San Diego. There, sick patients could take in fresh air in a warm climate — thought to be one of the most effective treatments at the time. This slice of California became so rife with tuberculosis treatment centers that it even became known as the “sanatorium belt.”

Fueled by the fear of tuberculosis, updated ideas of hygiene influenced how many Craftsman homes were built out, too. At the Gamble House in Pasadena, for instance, each member of the well-heeled family — the scions behind Procter & Gamble — slept in twin beds on their own “sleeping porches” outside, an arrangement thought to be more sanitary than snoozing inside.

Holding down the Fort

Writer and historian Candolin Cook examines the many eras of New Mexico’s famed Fort Stanton, including its multi-decade stint as a federal sanitorium.

Fort Stanton’s isolated location and existing infrastructure made it an ideal candidate for a sanatorium. In 1899, it reopened as the nation’s first federal sanatorium, servicing TB-afflicted merchant marines. A 1904 El Paso Herald article touted the facility as a place where “fresh air, outdoor exercise, and proper food take the place of medicine.” Over the years, Stanton became a state-of-the-art treatment center known for innovative approaches, such as housing patients in tents year-round and implementing a 4,000-calorie-a-day diet to combat the disease’s wasting effects.

Patients spent their days convalescing in cots on the hospital’s porch, playing croquet on the parade grounds, or engaging in occupational therapies like woodworking and ceramics. Gallows humor also helped them cope. In September 1905, according to the Des Moines Register, Fort Stanton’s Lungers’ Club initiated new members by having them demonstrate “deep, sepulchral coughs” while their brethren waved metal sputum cups in the air.

For more on this topic, be sure to check out this El Palacio Q&A featuring insights from Fort Stanton Historic site manager, Dr. Oliver Horn.